Temporary Microservice Pattern

Description and Reflections on Service Patterns 01 Mar 2022Introduction

I’ve been preoccupied with miscellaneous things in life making it hard to write blog posts in the past few months, but I’ve worked with a pattern and couldn’t help write about it.

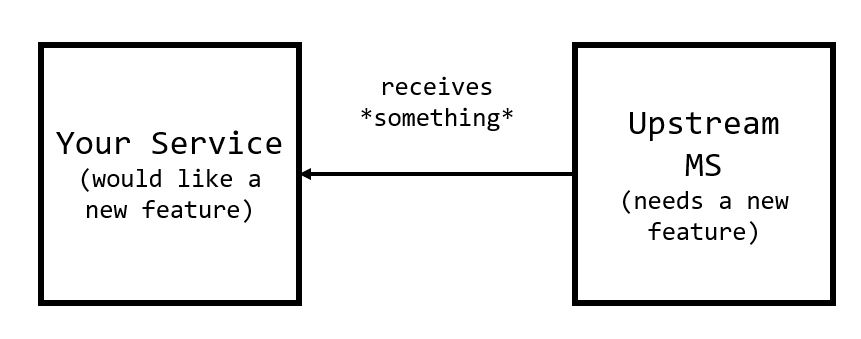

The pattern occurs when one service (lets call DownstreamMS) is blocked by another (UpstreamMS), and our UpstreamMS team cannot help us because they have their own issues (not enough manpower, different priorities, system design disagreements, etc).

There’s a handful of potential solutions, but one pattern is to introduce a temporary “middleman” service (TemporaryMS) that implements the necessary functionality. The idea being that this temporary service will be maintained and deployed until the upstream service implements these features themselves.

I haven’t seen any book/documents outlining this pattern (granted maybe I haven’t read enough or know the right name for this), but I thought I would outline the contexts and some pro-cons from my experience.

Context & Other Solutions

For a while, I struggled to come up with a general, yet relatable scenario to describe this “situation” without leaking work details. Then I remembered this video:

In the context of this video, our senior engineer could remove this blocker by implementing and deploying an ISO timestamp-converter-service that exists outside of Omegastar - and take it down once Omegastar “gets their shit togther”.

Satire aside, implementing “minor” behavior changes between two different APIs can be surprisingly difficult because of a handful of small headaches. For instance:

1. Mismatch in priorities or manpower

I’m sure we all have moments where we would like X team to implement Y feature or fix Z problem. Unfortunately that team has a lot of other critical priorities, and not enough people meaning they can’t get to your tickets until $DEMORALIZING_AMOUNT_OF_TIME.

2. Subtle bugs/edge cases from either party

Moreover, small bug or edge cases can pop up that complicate the development cycle. These issues aren’t the end of the world, but they might be problematic enough to trigger a version rollback or cause the changes to be scrapped entirely.

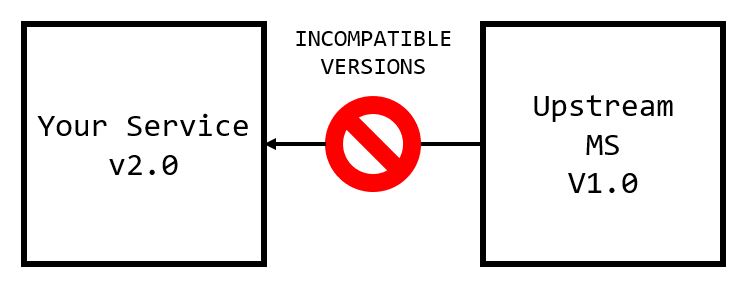

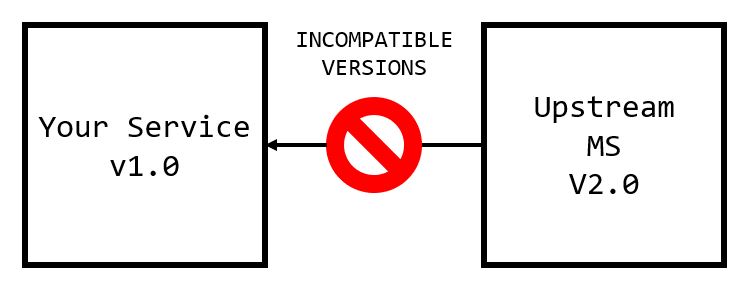

3. Coordinating the Deployment of These Changes

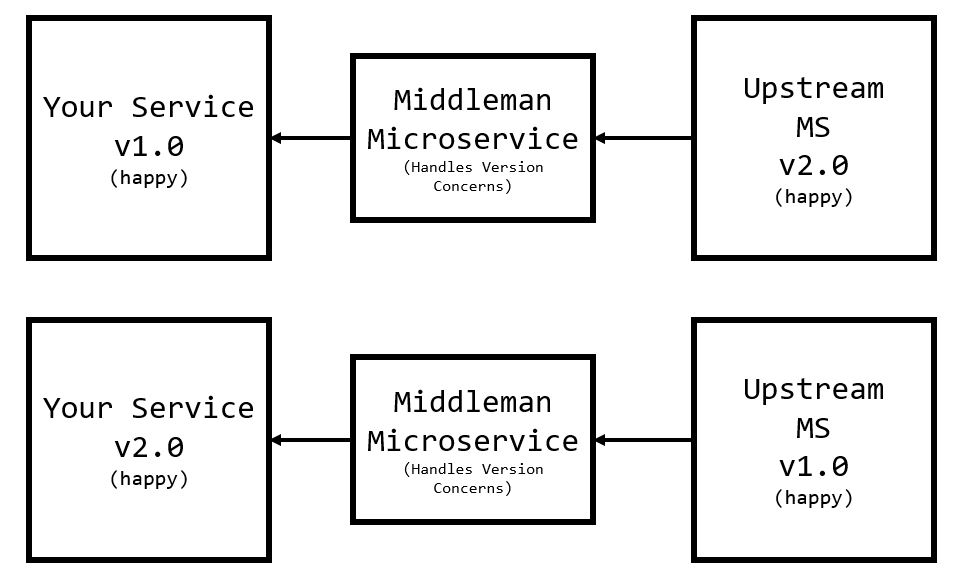

I imagine there are a couple of situations where teams accidentally deploy incompatible service versions at the same time like so1:

The headache is more likely to occur the further away the development team is from CI/CD (meaning teams need to manually cut releases or make release packages), and scales with the number of testing and production environments your team uses.

Possible Solutions

Individually, these aren’t serious issues because there are common solutions to each of these problems. For example:

1. Solution to the manpower/priority problem (D.I.Y)

If the UpstreamMS team is too busy, a member of DownstreamMS can program the changes on UpstreamMS and have their team approve it2.

2. Solution to the implementation problem (Comprehensive Testing)

We can avoid running into surprising bugs or edge-cases by making well-defined unit tests and integration tests.

3. Solutions to coordinating deployments

To avoid any surprise incompatibilities, we can extend our services by adding more API endpoints and versions (rather than changing existing ones), or implementing fallback behavior that depends on service version (via service registry).

Pitfalls

However, these solutions aren’t “no brainers” and come with their own set of problems.

1. Volunteering is going to be a lot of effort

The volunteering programmer will need to learn a new codebase as well as understanding its components to come up with a good implementation.

There’s a “catch-22” moment where if UpstreamMS team is already strapped for time, they probably won’t be able to consult or guide the volunteer on the “correct” approach.

If they are willing to sacrifice their time to give you the necessary details to start, you might be wrapping up a bigger portion of their teams’ time anyways.

Your pull request might have large waiting periods, where the upstream team is too busy to thoroughly review and critique your PR. Furthermore, if your PR doesn’t match up to their vision of the implementation (or is complete spaghetti), the other team will have to take even more time giving you the proper information to fix your PR.

2. Thorough Testing Is Hard

It’s really easy to fall into your own biases and come up with tests that

- don’t test everything

- badly test everything

After all, finding edge and corner cases is much easier in leetcode rather than real life. Unless you have a business expert on hand, a lot of effort will be spent on refining tests as different behaviors pop up.

3. Creating additional complexity

Extending services and implementing fallback behavior will increase service robustness, but end up increasing the complexity. Complexity isn’t the plague, but its acceptability is determined by the team.

4. Disrupting the development cycle

As an culmination of the previous three points, all of these factors can disrupt a team’s development cycle which can make your (or someone else’s sprint) incredibly wonky. For some teams that wonkiness is acceptable or expected, but for others it might harm their reviews.

Introducing a New Microservice

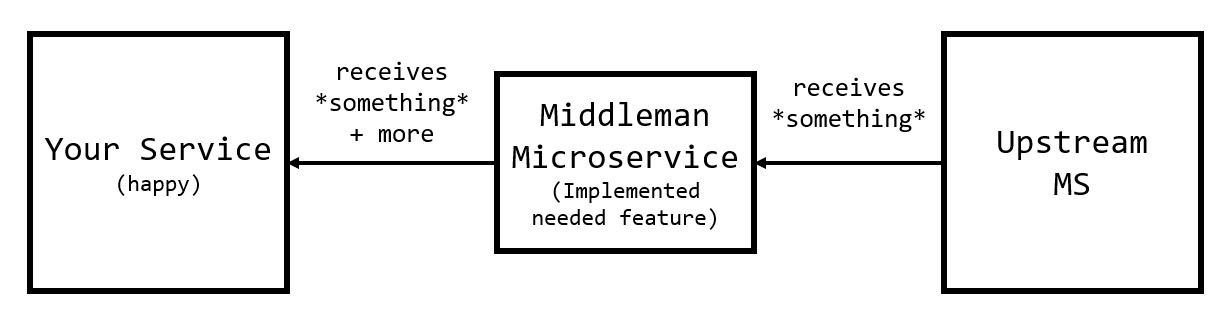

Creating a new microservice lets us circumvent some of the problems we see in the previous sections.

A volunteer from DownstreamMS won’t need to learn the internals of UpstreamMS, potentially speeding up development of the minor feature.

While we can’t do anything about testing quality, both parties don’t need to worry about deployment coordination. By decoupling the feature from UpstreamMS into its own service, the team’s respective APIs don’t need to be in sync. As a result we can change TemporaryMS microservice without affecting the UpstreamMS - meaning we can enter the integration testing phase much faster.

Because TemporaryMS is meant to be temporary, we can justify its existence until everything is in place.

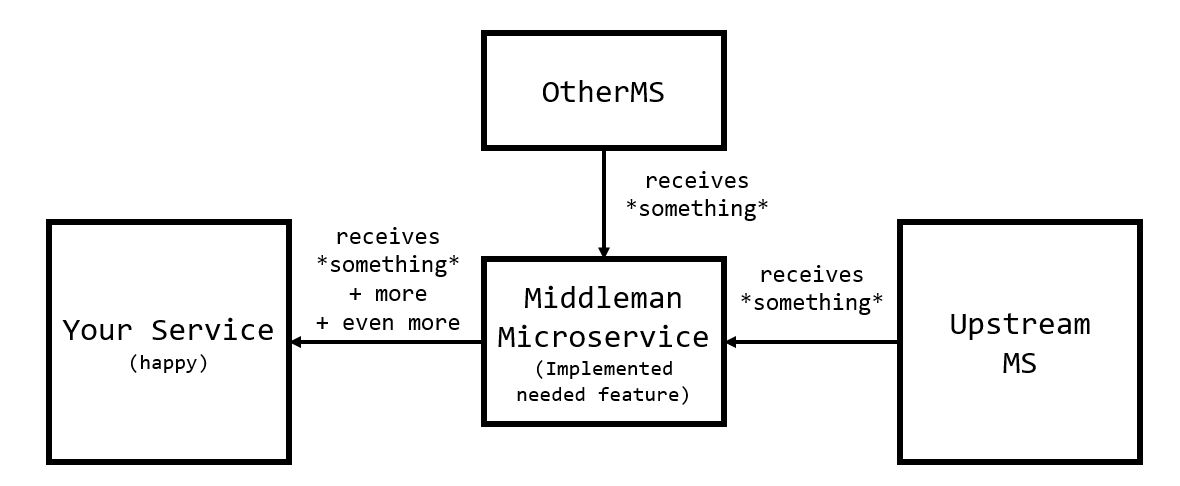

Employing the middleman pattern lets us introduce crazier dependencies because we aren’t changing the scope of the upstream service. Although I wouldn’t recommend it, we could supplement the data from our UpstreamMS with information from OtherMS as easily as this:

A new service is not a free lunch

Despite the pros in the previous section, making and deployment is not “free”. Depending on the tooling and documentation, deploying a new microservice can be:

- mindless (someone else can do it or there’s plenty of tooling to support developrs)

- medium effort endeavor (need to make configuration files and work with deployment tools)

- complete misery (your environments are configured esoterically and it’s a point-and-click adventure game of finding the right people/documents that can help)

Not to mention that compute is not cheap - the DownstreamMS needs to use this service enough to justify provisioning and eating the cost of compute3.

Ownership and maintenance are also concerns. Who will be responsible for maintaining the service? Will this TemporaryMS actually be temporary, or will it become a piece of “legacy technology”? Just because someone commented //this is a temporary solution, TODO: make better one doesn’t mean it will be retired in a timely manner.

Conclusion, Reflections, and Rambling

This pattern is neat and demonstrates the flexibility of microservice architectures, but I think this solution feels a bit inelegant.

We’ve added complexity to the systems topology4 as well the overhead of a new service for the benefit of being able to work faster. Obviously I would love if the simplest, easiest, purest solution could be done out of thin air, but other priorities just prevent this from happening.

Accepting the Microservice Philosophy

My first reaction to a project was me lamenting how I was creating such a “small” service. One principle of programming is reuse code by looking for the right “abstraction”. Rather than trying to hardcode for individual cases, we want code that is flexible and can handle generalizations. Deploying single-use code to do one niche task feels a bit sloppy, BUT is a sacrifice that lets us streamline other aspects of the development process.

Is this a practical solution?

My biggest fear is that someone reads this article and thinks, “there’s no way this would ever be applicable to a real software engineering”. To convince the reader (and keep details vague), there was a situation where our services needed an overhaul of some Upstream Business Logic, but the earliest the Upstream Team could make the change was three years later. Obviously this was unacceptable for our product launch, so we created a temporary, middleman service to handle the conversion of the business logic.

In this context, this change would be a part of a big software migration/rewrite, and the skeptic might point out that the company is forcing an unnecessary rewrite/migration. Joel Sposky has a great essay on legacy software and rewrites, and he outlines that rewrites can be killer moves because although legacy software is hard to understand and complicated it works and is well tested.

My philosophy is that we need to take a more holistic approach to understanding software. On the surface level, if the code works, it works. BUT If the code is making other aspects of development, integration, maintenance, or deployment difficult maybe the code has become “broken”. I can’t imagine a world where you need to spin up a WindowsXP VM in order to support a legacy backend, or forking over tons of money for legacy hardware (like mainframes) or software is an “okay” pattern. In the context I was working in, this piece of business logic was incredibly brittle and sometimes did not work. Even if I wanted to, I didn’t have the necessary access or authority to make changes on this software. Other aspects of the business weren’t able to extend the functionality, and were forced to reuse the same bits and pieces over and over again - something I would warrant as “broken”.

Anyways Happy March!