Better Testing with Environment Composability

(and other Forbidden Techniques) 02 Jul 2022Introduction

The motivation for this blog post is pain1.

Software development can be painful because testing well & thoroughly is tedious and exhausting (there’s a reason why QA is usually a full-time job). If you find testing easy, (1) you might not work with complex software or (2) you are the source of bugs.

Regardless of whether a company has scaled up their development & testing processes, the developer still needs to ensure the correctness of their code.

In service oriented architecture, this tends to suck for developers (you), because testing complexity scales with dependencies (other internal services, external APIs, databases, queues, etc). There are painful moments where the developer has to deal with cumbersome setup processes, or rely on mocks, or write even more code just to do basic testing.

Despite the increased number of headaches, there are ways that we can leverage service architecture and development environments to break away from this slog, and test “better”.

Short Story: “Testing: A Tragedy”

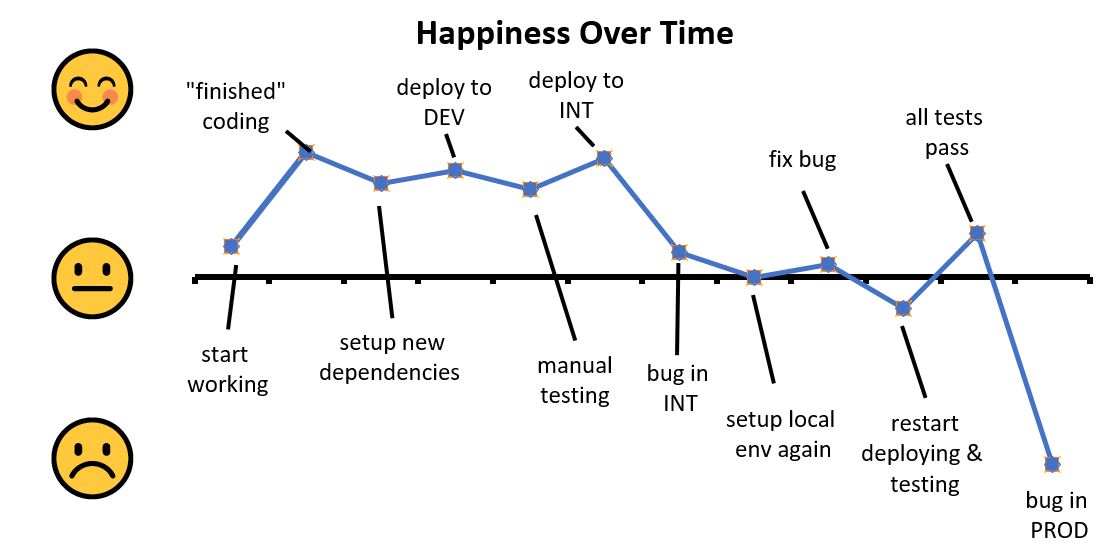

Originally this section was dedicated to a story. The gist of the story is that testing comes with a lot of little & large frustrations that are too difficult and erratic to describe, you just need to “feel” them.

I wrote it to illustrate the testing experience within large service architecture to try to provide context for this post. I also wrote it because it was difficult to communicate the little & large developer frustrations - unless you’ve already run into these frustrations professionally. I cut out it because the story’s length and tone was distracting from the actual purpose of this post The story is too long, too boring, and too difficult to make good, so I decided to cut it out of this post and quarantine it to a different post. Feel free to read it, but it’s incredibly boring and disorganized.

Reviewing “Testing: A Tragedy”

Aside from my poor creative writing skills, this story is a boring, frustrating, and repetitive because testing can be boring, frustrating, and repetitive.

Development for a well-meaning (but relatively green) developer is incredibly boring or frustrating. In my initial drafts of this post, I struggled to “objectively” explain the pains of testing, but every explanation was clunky because it ignores the “human” experience. the audience remembers the “micro-frustrations” and inconsistencies when trying to test their own software. While seemingly trivial, aspects like setting up, introducing outside dependencies, testing locally add unnecessary friction and stress that’s outside of the actual coding and testing process.

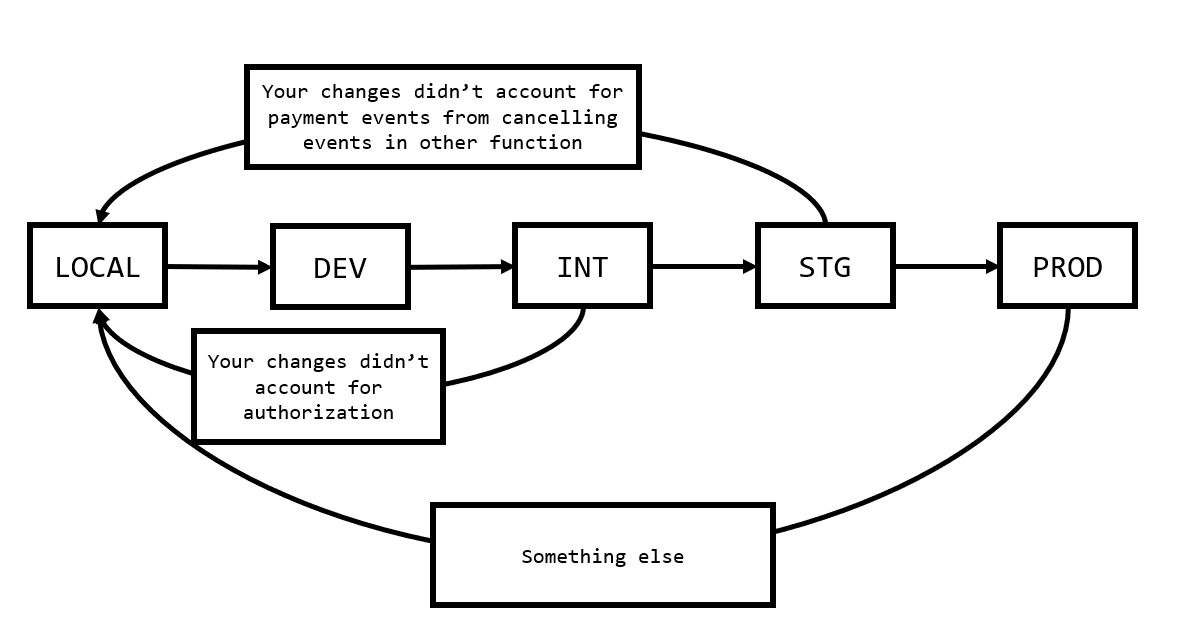

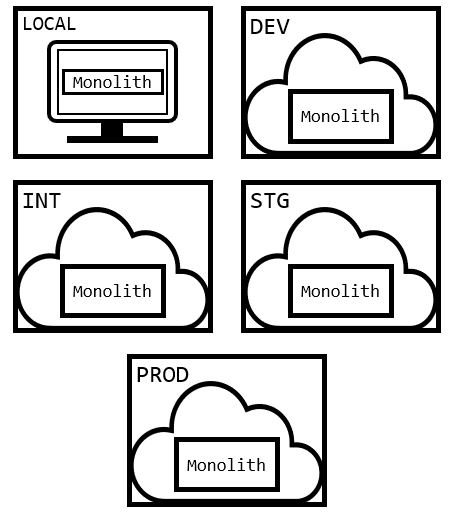

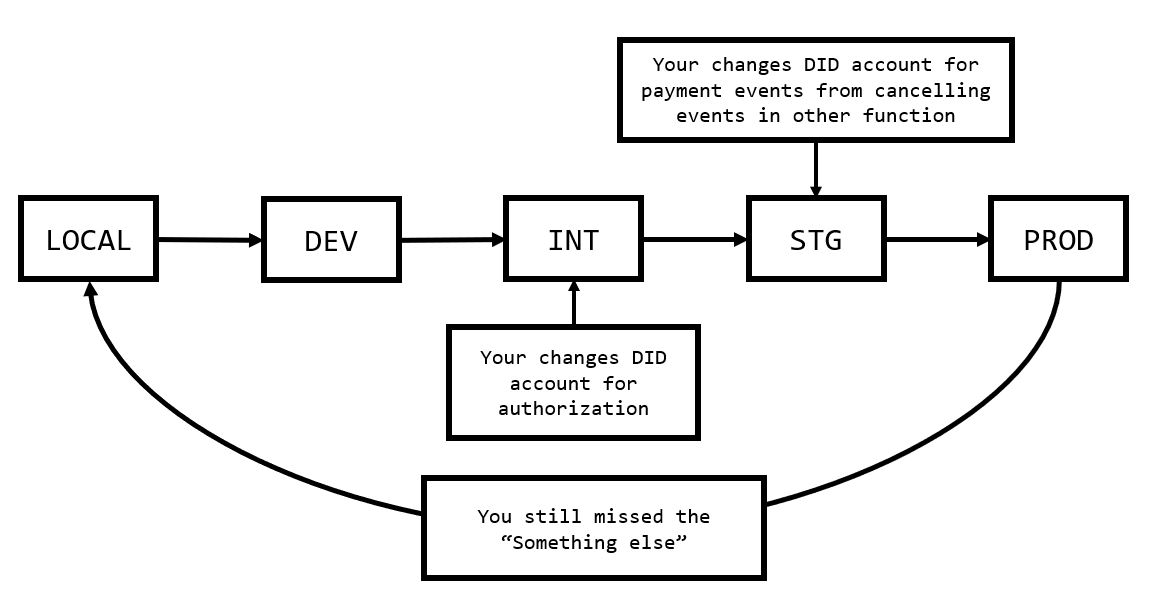

I also wanted to point out that the development cycle for these changes is incredibly wonky. Software bugs have slipped through because the environments couldn’t catch the “gotchas” of productions. In a monolithic architecture, the development, testing, and deployment of our code would look something like this:

Every time a developer found a mistake, they would need to restart from scratch and progressively moving their changes through the environments. This is fine because environments are designed to test and verify behavior as well as catch bugs - progressively higher environments also model more realistic behavior. However, depending on the frequency and processes around deployments (git flow releases vs CI+CD, permissions required to deploy, etc) - this can significantly slow developer output. A one day delay between deploying a branch to INT or DEV adds an extra day where a developer is stalled from working on a feature.

Finally, we have the idea that a senior engineer could have caught (obvious or obscure) bugs from reaching production, if they carefully reasoned through their PR or personally tested the feature branch. Relying on the senior to personally catch all your mistakes (outside of code review) is not a scalable practice. Seniors have higher priorities and won’t be able to thoroughly review and ensure everything is correct - the more popular or important the product is the busier senior gets. At a certain point, junior developer should be able to figure out, find, or predict bugs through their own testing.

Moreover, the senior engineer is only human and also capable of pushing bugs to prod themselves…

Work Smarter Not Harder (The Solution)

The issue is that it’s difficult to reliably and realistically test software because emulating behaviors and bugs heavily relies on the environment.

I’ve had issues with bugs that couldn’t be reproduced “locally” because its dependencies couldn’t be mocked. Or situations where request flows are locked by dependencies. For example, some dependency (like authentication, payments, data) can lock you out of testing certain flows or situations or is unable to behave the way you want it to. Or maybe a difference in dependency version changes some underlying behavior - subtly changing the correctness of your implementation

It feels like it’s impossible to get remotely close to “production ready” code without merging and deploying changes into higher environments 2. The result is to compromise and merge something that the developer understands is reasonably imperfect (with the expectation for more amendments to be made). However, this is a sloppy and risky habit that was necessary from the “monolith” days - when our environments were single a hunks of immutable code where everything needed to be in the right place at once.

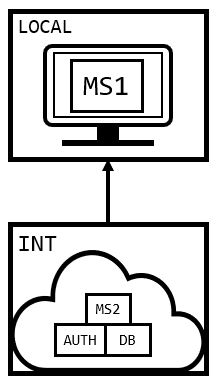

However, we’re using microservices now (cue sarcastic fanfare)! We can actually leverage some of benefits of service architectures. One of them being that developers can now treat the environments themselves as composable components that we can mix and match to satisfy unique testing situations faster!

What does “treating our environments as composable components” mean? It means that instead of running local dependencies or mocks, we source our dependencies directly from other environments (DEV, INT, STG, etc).

In this approach, we have access to realistic, predictable behavior of services in higher environments, without having to actually deploy changes to these higher environments.

The process of testing & deploying environment by environment only to have to restart locally is over! Freeing us from (some) of repetition of testing. Developers can predict and discover bugs “early on” without having to make embarrassing PRs over and over again (“haha I missed a bug so i need to redeploy laugh in pain”).

Compared to our previous workflow, it now looks something more like this:

We won’t be able to catch all of the bugs and not everything can be hooked up like this, but it’s a start.

The Execution

Moreover the execution of this development pattern is easy. It just requires changing some configurations within your local services like this.

From a configuration like this:

{

"timeout": 1000,

"upstream_service_1": "http://****:8001",

"upstream_service_2": "http://****:8002",

"upstream_service_3": "http://****:8003",

"feature_toggle_1": true,

"feature_toggle_2": false

}

To a configuration like this:

{

"timeout": 1000,

"upstream_service_1": "http://INT_UPSTREAMSERVICE1",

"upstream_service_2": "https://****:8002",

"upstream_service_3": "http://INT_UPSTREAMSERVICE3",

"feature_toggle_1": true,

"feature_toggle_2": false

}

I will note it won’t always go as easily as described. Sometimes the environment is going to require a special authorization, or some SSH Tunnel, cloud credentials, etc.

Implementing development patterns like this can let you discover unexpected behavior early on, inject service behavior, mix environments, or even perform forbidden techniques.

Behavior Injection

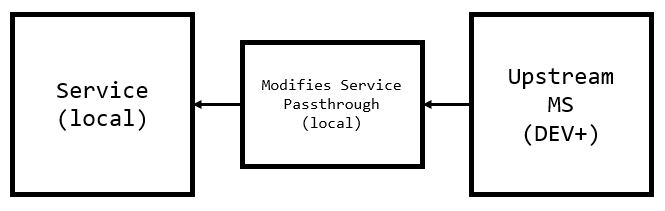

With these patterns we can easily modify, augment, or change behavior through pass through/middleman services. If we need to account for a new responses, headers, etc from dependent services from higher environments - we could easily sub in the information we need.

// Hypothetical code for what this could look like

// probably should use reverseproxy from the net/http/utils

package main

import (

"net/http"

)

const ORIGINAL_SERVICE_ADDR string = "http://..."

func modify1(w http.ResponseWriter, req *http.Request) {

// Do the things you need to

req.URL = ORIGINAL_SERVICE_ADDR

resp, err := client.Do(req)

// Do the responses

}

func modify2(w http.ResponseWriter, req *http.Request) {

// Do the things you need to

req.URL = ORIGINAL_SERVICE_ADDR

resp, err := client.Do(req)

// Do the responses

}

func main() {

http.HandleFunc("/passthrough1", modify1)

http.HandleFunc("/passthrough2", modify2)

http.ListenAndServe(":8080", nil)

}

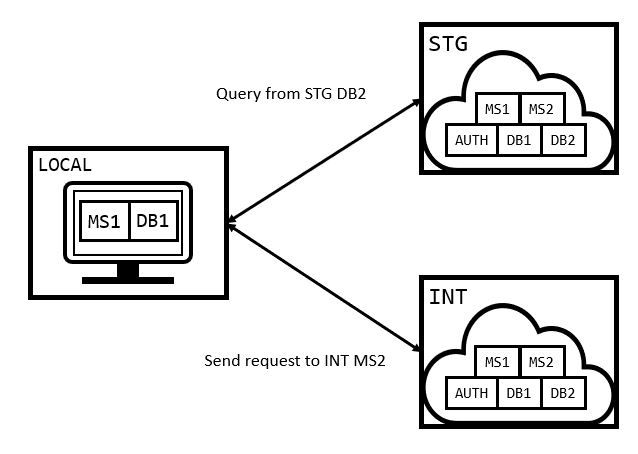

“Frakensteining” Environments

If for some reason we need random things from random environments, we could mix environments as well (like mixing a local service with a STG database and DEV authorization service). By mixing several environments we can grab specific behaviors from specific environments, at the huge risk of not getting in realistic tests.

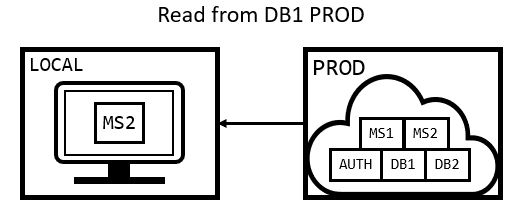

The Forbidden Technique: Using PROD

A really degenerate technique someone can use is connecting a local service directly to a production dependency. As a disclaimer, you should not really do this. You should never be writing to production for any reason, and only use READ-ONLY operations. However, reading from production can help you effectively investigate production behavior as well as guard your service from “production-level” wonkiness.

Conclusion & Drawbacks

This testing methodology is “better” in that there’s less frustrations and we can observe/tackle certain classes of bugs earlier on. However, it’s important to acknowledge all of the ways this method falls short.

Manually testing this way is not a remotely scalable or stable testing methodology. Ideally, there should be processes that automatically test changes every step of the way. We also will probably need some unit tests, or mocks, or E2E.

It’s also really important to note that we cannot use this method to drive development. If we were to develop our code around this method (rather than developing around specifications) - we’re essentially writing junk code for rapidly changing/unfinished software.